Trust Models

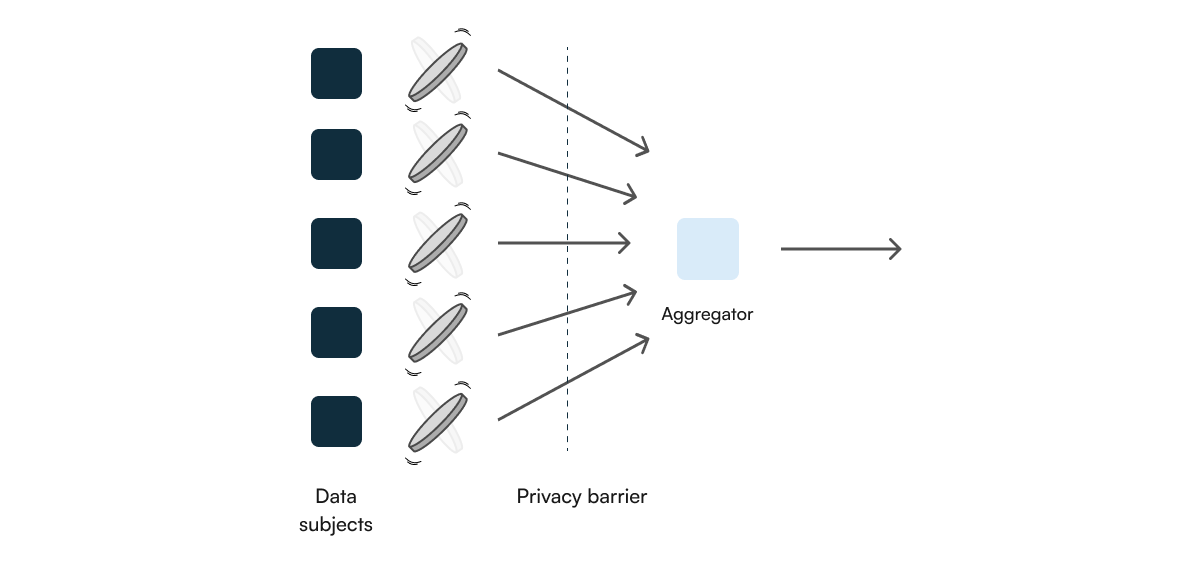

The Local Model

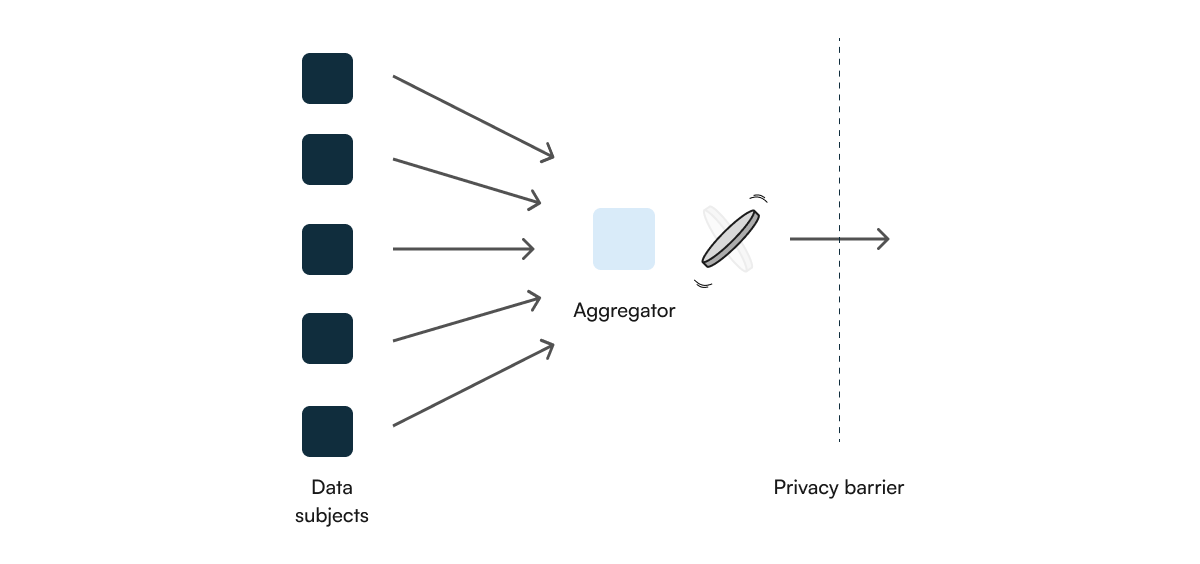

Since the noise is added very early in the pipeline, local differential privacy trades off usability and accuracy for stronger individual privacy guarantees. This means that while each user’s data is protected even before it reaches the central server, the aggregated results might be less accurate compared to global differential privacy where noise is added after data aggregation. In local differential privacy, each data subject applies randomization as a disclosure control locally before sharing their outputs with the central aggregator.

The Central Model

Trusted vs Adversarial Curator

When we define a threat model, we mainly focus on how much trust we place in the curator. A trusted curator is assumed to apply DP in a correct manner, while in contrast, an adversarial curator may (and we assume it always does) attempt to breach privacy.

As such, these concepts are strongly related to the locality of our DP model, which we previously defined as local and global DP. For the local DP protocol, we place no trust in the central curator, thus we can perfectly accept a model where the curator is adversarial, since the privacy guarantees are put in place by the user in a local manner. On the other hand, for global DP, we expect the curator to set these privacy guarantees in place, and as such we place all the trust in them.

Static vs Interactive Releases

These two concepts refer to how often we publish DP statistics. A static release involves publishing a single release with no further interactions, while interactive releases repeat these processes, for example, by allowing multiple queries on the dataset. Static releases are simpler, but interactive releases could offer additional utility, but require a more robust privacy measurement for each query due to composition.

Event, Group and Entity Privacy

An important aspect of differential privacy is defining what it is we are endeavoring to protect. Ultimately, we usually are trying to protect the atomic data subjects of a dataset: people, businesses, entities. However, depending on the dataset itself, rows of the data table may refer to different things and individual subjects may have a causal effect on more than one record.

Group privacy refers to settings where we have multiple data subjects who are linked in some manner such that we care about hiding the contribution of the group. An example of this might be a household in the setting of a census. Finally, there is entity-level privacy. Similar to group-level privacy, this is when multiple records can be linked to a single entity. An example of this would be credit card transactions. One data subject may have zero or multiple transactions associated with them, thus in order to protect the privacy of the entity we need to limit the effect of all records associated with each entity.

From a technical perspective, the mechanics of the tooling to deal with groups and entities are the same so their terminology is often used interchangeably.

Multiple Parties and Collusions

Involving multiple parties in DP releases requires additional accounting of the privacy budget, and similarly to how we described an adversarial curator, we now focus on defining a group of analysts, which could adversarially collude against the DP release.

As a more practical example, collusion typically refers to an environment where multiple analysts are allowed a set privacy budget, but they collaborate between each other to leverage composition and produce information about the dataset that is protected by a worse epsilon parameter, and thus breaking the intended privacy budget allocated for them.

Periodical Releases

This concept, often also related to the “continual observation” area of study, involves producing multiple differentially private releases for a dataset that is periodically changing. Achieving this can be challenging as each release must be carefully accounted for in the privacy budget, and organizations that allow for DP analysis of continually updated datasets, as some of the ones present in our table, are mindful of setting budgets for both the user and time level.